INTERVIEW: Daniel Kaluuya, Lakeith Stanfield on JUDAS AND THE BLACK MESSIAH

- John Cotter

- Dec 30, 2021

- 7 min read

(Originally published in THE KNOWN)

The voices that preach must be held by bodies that support the message. When that voice is taken away, it leaves a void of hope and action behind it.

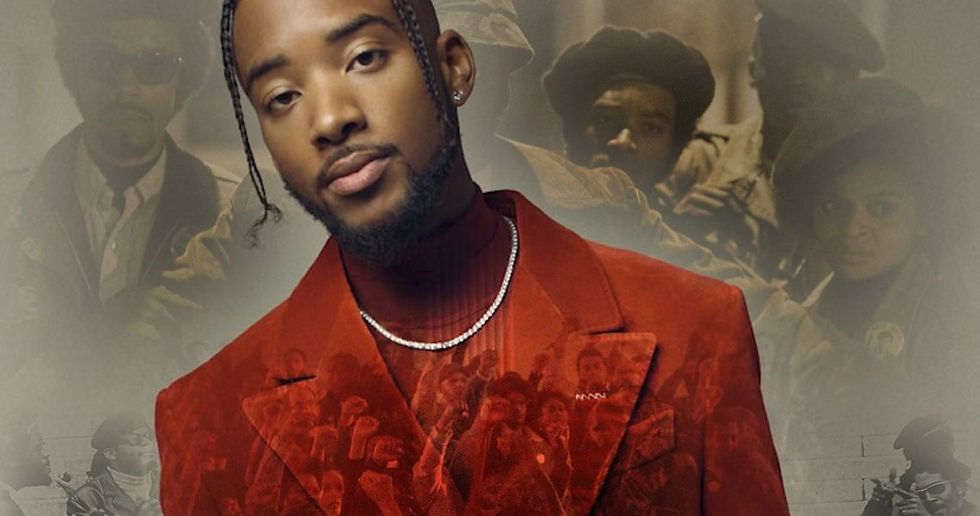

This is how Daniel Kaluuya explained the legacy left behind by Illinois Black Panther chairman Fred Hampton, who the actor portrays in Judas and the Black Messiah. I got the chance to talk with Daniel Kaluuya, Lakeith Stanfield, Dominique Fishback, and Algee Smith from the film about a multitude of topics that all seemed to circle back to a collective intention of telling this pertinent tale with the integrity it deserves. The historical drama is set in 1960’s Chicago and chronicles Hampton’s rise in the Black Panther Party alongside the FBI’s attempt to infiltrate the party and its influential leader, with the fed’s having a man on the inside. William O’Neal was this insider who was initially caught trying to impersonate a federal agent, just for him to go back to impersonating a citizen. This irony is not lost on the film’s vision, with writer/director Shaka King embracing this and the full complexity of these conflicted characters.

But they aren’t just characters, these are real people being interpreted and dramatized for effect, but not purely for entertainment’s sake. The unified efforts to uphold Hampton’s memory never get in the way of making it entertaining; it all feels incredibly organized from the start.

It can be a goal as much as it can be a faithless hurdle for most biographical films to try and balance entertainment and delicate history. For Judas and the Black Messiah, a hurdle was never in the realm of possibility, with Fred Hampton Jr. and Akua Njeri (previously Deborah Johnson) approving and even being continuously involved with the project. But not every figure was able to have a detailed history on record, notably William O’Neal, played by Lakeith Stanfield. He gave me some insight on this when I asked about the balance of respecting history and enacting creative freedoms as a performer.

JOHN: Bill O’Neil is quite a cynical character to look at from where you started to where you ended. A lot of your performances have had so much creativity pumped into them, Sorry to Bother You, Atlanta, and even Knives Out, it feels like you got so much creativity in what could have been a rigid role. Now here, you’re representing a real story. Sort of that dramatic irony of the audience knowing that you’re deceitful, but everyone in the Black Panther party does not. Now playing a real role like this, do you still feel like there are creative freedoms that you get? LAKEITH STANFIELD: It depends on the circumstance, the character, and the director that you’re working with. Shaka allowed us to exercise our artistic freedom, which is dope. A lot of people don’t really give you that freedom to be able to explore

the character and want to stay rigid to what’s on the text. But for William O’Neil, there wasn’t really a lot for us to draw from, cuz’ he had been dead.

A lot of it was interpretation. In his long-form interview, Eyes on the Prize, I got a little indication as to who he was. But that was only an hour from his whole life. I had to try and draw from that and create a character based on limited information and what I felt to be true. You know, you can’t be around somebody like Chairman Fred Hampton and not be moved by what he was bringing to the table. O’Neal even said in the long-form interview that, “I feel bad about what I did, but I had to continue to play the role”. I kinda’ took that and rolled with it.

William O’Neal’s government-sponsored upheaval of the Black Panther party is as much an inciting incident of the party’s untimely downfall as it is a reminder that he was more a product of unjust circumstance than autonomous decision-making. We never get much reasoning as to why he was impersonating an FBI officer in the first place. Rather, we understand the desperation that can lead one to that situation.

The sympathy that we have for him in the beginning perpetually diminishes, as the Black Panther party’s fall is shown to be exponentially tied to O’Neal’s rise to financial and social freedom (on the FBI’s terms). William’s actions were the antithesis to what Fred Hampton represented: liberation, freedom, and the simple human desire to be a skeptic.

This on-screen representation of Fred Hampton sits on the shoulders of Daniel Kaluuya, whose portrayal of the activist has a rather authoritative effect, gaining our immediate attention and suggesting that he was never skeptical about taking on such an essential role.

Where hesitance was absent, curiosity and introspection were present, specifically when taking on the role of a revolutionary, trail-blazing figure whose life story deserves to be heard and understood by the masses. Grasping the rippling effects of Hampton’s legacy while simultaneously portraying him is an artistic paradox of unthinkable proportions. Thankfully, Daniel Kaluuya unboxed this for me when I asked about what a figure like Fred Hampton would mean for a city like Chicago today.

JOHN: We were just talking to Lakeith before this, and he kind of talked about Fred Hampton being such a big voice for the people of Chicago back then, but something that is truly a void now. We don’t have that voice in the city, or any voice like we used to. It’s really hard for people in the city to trust public figures.

Fred Hampton is someone who balanced the line of being pandering and commanding, as his speeches were so powerful but they were never self-absorbed . They pulled upon what people wanted in the Black Panther party and gave reason and voice to that collective emotion; a reflection on the needs and desires of those within. Looking at Chicago right now, what’s something that someone like Fred Hampton could bring to a city that has been so bogged down by injustice? DANIEL KALUUYA: It’s something that I didn’t really confront while starting the prep, thinking like “Wow, I’ve been affected by Chairman Fred’s assassination.” Just inside about the fear of telling the truth and saying something. Kind of going “there’s a cost for that.” You might get hurt, you might get punished, you may get this, you may get vilified. There is just something in me. I think it’s just a generational thing, you know? So, I just believe in conversations not classes. I feel that people need to conversate and share ideas and spend time with each other and let that grow organically, and the person will present themselves.

Chairman Fred isn’t like a star, he came out of a universe of people. The fact that he loved everyone around him, the conversations he was having with people around him and the time that he was spending with people around him. We’re shooting the film and it’s a brief segment at the beginning. He’s like “Yo, free your minds for less than a quarter.” He’s out there giving out newspapers, he’s out there with the people.

That thing where it’s about understanding that it could be any of us! It’s not like he’s this star child, he was any of us! It’s about when you identify someone, and he was part of a larger body. He was the mouthpiece of this larger body. People go “We ain’t gotta' mouth, we ain’t gotta' mouth.” Let’s make the body! So then the mouth presents itself. That’s how I see it.

If we focus on “We need more mouths, we need more mouths,” we’ll just have loads of mouths not connected to anything. What are they saying? Who are they saying it for? It’s about going “Alright, we need to come together, unite, and have a philosophy.”

Then, we can question who’s saying that, we can articulate what they’re saying and what they believe. It’s about oneness and creating oneness in terms of values and priorities.

Unifying around mutual intentions is a driving force for any successful artistic endeavor,

as the cast’s concentrated dedication is reinforced with each actor I talk to. Following Kaluuya’s poetic response was a talk with actress Dominique Fishback who portrays Deborah Johnson in the film, Hampton’s partner and mother of his child.

But sticking her with these labels would be as much a dishonor to Fishback’s performance as it would be to the integral role that a mother like Johnson plays. Stabilizing the sacrifices that come with motherhood and being a Black Panther in the late 60’s is a triumph that Fishback delivers with force in Judas, humbling Hampton within intimate scenes of humility and openness that contrast his roaring speeches.

It would be difficult to appreciate the emotive moments if they were not convincing or passionate, which Fishback explained was partially due to the relationship she built with Kaluuya before-and-during filming when I asked her about this dominant performance.

Comments